Celtman Xtri – Rounding off 10 years of Long Course Racing

I’ll say it right at the start – Celtman is one of the best races I’ve ever done. The challenge, the distance, the stunning scenery, the camaraderie.

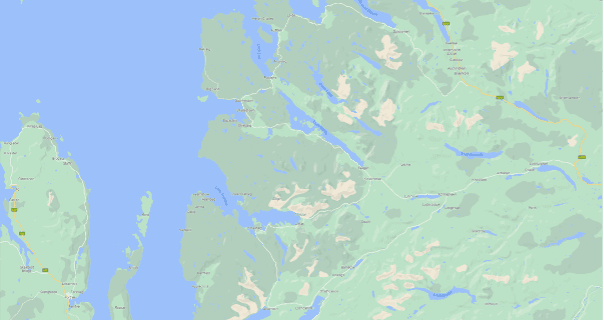

Celtman is an ‘Extreme Triathlon’, part of the Xtri World Tour. Xtris are long-distance races with typical distances of around a 3-4km swim (usually in cold water), a 200km bike, and a marathon, but with the twist that there are usually a couple of mountains plonked on the run course. So it makes the race longer, and many would argue harder, than an Ironman. Celtman takes place in the north of Scotland, on the mainland between Skye and Ullapool.

It’s a beautiful, wild, remote part of the world with changeable and unpredictable weather and conditions so entries are capped at 250 people, as the remoteness of some of the sections of the enormous bike course, and the need to keep people safe on the mountain prevents more than this number. Entry is via a ballot system, with the results only arriving six months before race day. The other deviation from ‘normal’ long-course racing is the need for a full support crew. Every competitor has their own support vehicle on the bike leg and a support runner on the mountain, as the course is spread over too wide an area for the organisers to provide centralised feed stations or mechanical assistance. The support runner is especially vital as they can carry a lot of the athlete’s nutrition and hydration and to ensure that they (who have already swum over 3km, biked over 200km, and done around half the run) don’t do something silly like step off a mountain because they are not capable of making a sensible decision.

I’d settled on Celtman as my big race as it was a rather notable year for me as it would round off a decade of Iron and long course events* – 10 from 10… and would also mean that I’d managed to get round England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

*2014 – The Big Woody (Wye Valley, UK)

2015 – IM Copenhagen (Denmark)

2016 – IM Mallorca (Port de Pollenca, Mallorca, Spain)

2017 – Cotswold 226 (Ashton Keynes, Wilshire, UK)

2018 – IM Wales (Tenby, Wales)

2019 – IM Ireland (Youghal, Cork, Ireland)

2020 – IronBan (Middleton Cheney, Banbury, UK)

2021 – IM Bolton (UK)

2022 – IM Copenhagen (Denmark)

2023 – Celtman! (Torridon, Scotland)

Thus when I got news of a successful ballot entry I was hopeful of polishing off the ‘full set’, but nervous as I didn’t feel remotely ready to take it on for a number of reasons - mostly revolving around having not done nearly enough training due do a seemingly never-ending sequence of illness and injury.

So the list of excuses worthy of F1 drivers:

September 2022 – I got Covid. Really badly. My first time with the virus and I was flat on my back for three days and it took weeks to be able to walk the dog up a hill, let alone regain fitness for a race. I was feeling great after IM Copenhagen but having just hammered my immune system flat with the IM proceeded to get on a plane with 200 people to fly home… inevitable really.

November 2022 - I’d just got back on track and was finally feeling good when I was struck down again (Covid negative but something awfully like it) which knocked me out for another 6 weeks or so.

December/January 2022/23 – Once again having just about started feeling better I went away over Christmas and was ‘topped up’ with a vile cold possibly gained from the children at a family gathering.

In May, with just a month to go, I broke my finger. A young chap riding a bike without functioning brakes railed it round a blind corner on a cycle path, panicked, and his heavy bike used my hand as a deceleration tool. With a black and blue swollen finger it was agonising to try and grip a handlebar whilst riding, and swimming also was painful. After a couple of weeks I managed to adopt a strange style of crossing my fingers, with the bad one behind a good one, that allowed me to at least make progress through the water.

Throughout this whole time I was shunted from pillar to post with an agonising wisdom tooth which was finally extracted (after more than a six month wait) in February 2023.

So all in all not a fantastic run up to one of the toughest long course races in the world, but determined to proceed I began the planning, as rather more kit and people were required than for a normal IM. First of all the people – I must confess that I rather assumed that Annie would be on board (she had suggested I enter the ballot, so it’s her own fault really) and she was going to undertake Transitions 1 and 2 (more on that in a minute), and support vehicle driving and bike feeds. I also needed a support runner for the mountain – we did consider Annie doing ‘solo support’ – possible, but not recommended – so at a Team Cherwell swimming session I sidled over to Nick and began my campaign of asking/suggesting/pleading/threatening/begging/coercing to get him to come to Scotland. As he is clearly certifiable he actually agreed without too many bribes and so he was find himself awake at 1.30am on the way to the startline to ride shotgun in the van ready to leap out and supply bottles and food on the bike course, before being dropped off at T2a to accompany me up the mountain. (As I tried to stuff the required kit into the smallest possible running vest I was laying plans for him to go round the course with something approaching a Bergen, containing not only his mandatory kit, but the mandatory ‘shared’ kit – first aid kits, survival blankets and so on – but also extra hydration and nutrition.)

On Thursday we met up with Nick, who had just done the mammoth drive to North Scotland with a couple of hours nap in a layby, for a swim recce at the swim start location of Inverbain (a huge metropolis of 2 cottages). The swim was genuinely scaring me as historically I’ve never done well in cold water and thus I was wearing a neoprene thermal vest under my usual wetsuit, as well as neoprene cap, gloves and booties. The short walk across the foreshore was therefore sweltering, but once in the water many of my anxieties were eased. Whilst colder than I’m used to it was perfectly bearable with my extra layers, and whilst there were jellyfish they were not as numerous as they might have been. Nick and I swam out to the first island (from which you can see the second) and I was able to get an idea of sighting and a general feel for the water. We only did around 800m but it was a huge confidence boost and many of my nerves were calmed. We drove round the end of the loch to Sheildaig, where the swim exit and T1 would be, to have a look at it from the other direction.

After a quick lunch we headed on once more to Torridon – Race HQ and the eventual finish – for the kit check of the mandatory equipment we would have to carry on the second part of the run course. Friday we would be back there again for the race briefing, before heading back over the pass to the campsite to compile everything, have a short bike shakedown ride, and into bed at 8pm to try and get some sleep before leaving the campsite at a revoltingly early hour of the morning to arrive in Sheildaig around 3:00 to get the bikes racked, collect the gps tracker (to be carried from T1>finish) and the ‘dibber’ (to be carried throughout).

With everything racked it was time to get into my various layers of neoprene and board the buses to take the competitors to the remote swim start. Despite the early hour the atmosphere is electric – it’s the real deal – braziers, bagpipes, drums and the flaming Celtman logo, ramping up the atmosphere before you are called forward to wade into the dark water as the sun rises from behind the islands: waiting for the sound of the airhorn to set you off from the deepwater startline of two kayaks. It starts so early as: a) it is going to be a very long day out and its probably best to try and get everyone finished on the same day; b) the bike route is partly on incredibly narrow roads or on long sections of the North Coast 500 so its best to try and get out ahead of most of the traffic.

Having spent the previous six months being terrified of the cold water when I actually waded into the loch to get underway I was surprisingly calm. The success of the recce swim (and my newfound love of the neoprene thermal vest) had me bobbing around quite happily as everyone lined up ready to go. The airhorn sounded and we were away. Being a decidedly middle of the pack swimmer I prefer to avoid the fight that sometimes happens at the front of the field and stayed quite far over on the left of the course, preferring to take a slightly longer route rather than be swum over and clouted in the head. I had a spare pair of goggles on my thigh just in case my main ones got knocked off or broken. I’d also made sure to wear my goggles over the neoprene hat, but under the swim cap, just to keep them that little bit more secure. Even though it was 5:00am it was fairly light, and I’d carefully selected tinted goggles as we would be swimming east, towards the rising sun. Sighting was not an issue – no trying to aim for a tiny buoy on the horizon here – out round the end of one island, across to the end of the next island, and up the slipway. Easy to keep on track with a glance, rather than trying to pick out an inflatable marker. Conditions were perfect – millpond flat water, and the hoards of jellyfish that often fill the loch were not nearly so bad as they could have been. The jellyfish was another reason I was happy to be almost entirely covered in neoprene. I did hit a few (not all are stingers but it is still unnerving) and got a very minor sting to the eyebrow but even that had stopped tingling by the time I got out of the water. All this added up to having a (for me) rapid swim of 1h06m. I exited the water at the old slipway in Sheildaig, the Clann an Drumma band having hotfooted it round from the start to herald us out of the water.

T1 is where the support crew start their duties. The thermal vest fits very tightly and is virtually impossible to get out of without help, so Annie was in the pink supporter’s shirt helping me get out of the swimming gear. It’s a case of being prepared for all eventualities as the conditions can be so changeable and unpredictable that there was warm drink ready in case the cold had got to me on the swim, but in this case it was applying sudocreme to the minor neck chafe (which stung) and then really slathering on the suncream (which really stung) as I was going to be out on the bike with not a lot of shade for a while. At the same time Nick was starting getting me the nutrition – I’ve always done better on ‘real’ food rather than endless energy gels - so to top up the porridge that I managed to force down at 3:00am Nick handed me a chicken wrap in T1, to send me out on the bike in good shape. The team made sure I had the number belt, the GPS tracker (I was already wearing the ‘dibber’) and I had everything good to go and sent me on my way, whilst they gathered together my discarded swim gear, loaded it and set off on their journey.

The bike from my perspective was perhaps the easiest part to plan for. It’s the section that comes most naturally to me. The goal was to keep under 200 watts and not go over 300w on the climbs – keeping it really easy and not going off like a stabbed rat. If it feels way too easy at the start, its probably about right – keeping it consistent and smooth. [For those that are not familiar with using a power meter it’s a very useful tool for getting the most efficient bike leg possible. A triathlon bike leg is essentially a time trial. It’s not like a road race: there are no chasing attacks, or trying to make a breakaway. The more consistent one is the more efficient one is. The more efficient one is the faster one is. Power is measured in watts, and watts are an absolute – this is what makes them so useful. You can ride the same road at the same speed, on two consecutive days but your heartrate might be different because you had a cup of coffee, or a poor night’s sleep. Speed is not a reliable measure either: a headwind, heat, rain or anything can change it. But a watt is a watt. I cannot overstate how important smoothness and consistency is. I had my target of (under) 200 watts average: this could be achieved by doing 100w for a bit, then 300w for a bit etc… but one will be much, much faster if one consistently does 200w – it’s the changes in pace that knacker the legs. Ease back on the hills, keep it steady on the flats and keep recovering on any downhills.] Whilst long, 20km longer than a standard Ironman, the bike course is not actually overly hilly. There are 2200m of climbing (compared to 2600 at IM Wales, over only 180km) and they are mostly gradual drags, with a few longer hills, but not much that happens all in one go. For the first 30km of the bike leg the roads are narrow – single track with passing places, so there is no support allowed in this section, as not only are the athletes coming travelling along there, still quite bunched up from the swim, but the entire cavalcade of vehicles is trying to get along there as well – if a support car was to stop there would be a mighty traffic jam. I found it actually quite useful as making my way through the procession of cars actually kept me from going off too hard and it eased me into the ride. The plan was for the team to ‘feed’ (both give me food and swap my drinks bottles over) every 30km or so. As we were swapping bottles the team could keep an eye on how much I was drinking as, in the weather that Scotland is famous for, the temperature was rising to around 30°C and dehydration could be a real issue. My bike has a front bottle built in, that can be refilled on the fly, a bottle in the rear mount behind the saddle, and an aero bottle on the downtube. I was using some bottles of Precision Hydration (salt and electrolytes), some of High 5 energy drink and just plain water. The Precision Hydration was particularly important as not only do I sweat heavily but I’m a high salinity sweater (as the white salt marks on the back of my trisuit usually attest to) so replacing the lost salts and electrolytes would be really important. Nick and Annie had a list of the order that I wanted the bottles in and a supply of brioche and hot cross buns (real food again). The first feed was a steep learning curve – a slight downhill meant that I was carrying too much speed and I chucked my bottle away successfully (to be picked up by support of course) I dropped the new one. Nick and Annie collected the discarded bottle, leaped back in the van to make the overtake and as they passed me I shouted ‘Uphill! Uphill!’. 5km up the road the bottle was successfully picked up, the slight rise let me scrub a bit of speed off and Nick valiantly started his running early, moving uphill to make the grab easier. Every pitstop got easier.

After one where I had been handed a brioche I had managed a couple of bites but dropped it whilst navigating a rough piece of road. It actually landed between my arms on the tri bars and teetered there for several moments. I tried to reach down and grab it with my teeth without crashing, but it was just too far away. As soon as I shifted my arm it tumbled down to the road. As the van came past me I made strange grabbing hand movements, like a deranged lobster claw. Amazingly I found them a couple of km down the road with fresh food. It turned out that my wild gesticulations had been unnecessary, as Annie has spotted, and amazingly somehow identified, the remains of the brioche on the road whilst driving and realised that I needed more nutrition. It was hot. Really hot. I was sweating heavily and there was always a sheen of moisture on my arms – I was losing water as fast as I was taking it on. The support crew realised this, and dropped the feed intervals from 30km to more like 20km – a good call. The main plan was for just over halfway – around the 120km mark - I would have a ‘big feed’. I’d stop, get off the bike, have a chicken wrap and generally reset. I usually get a low point around this point on the bike. You’ve done a lot, and there is still so much more to go. The crew had found a good, shaded, spot at 108km in, so there we stopped for the big feed. I had the wrap, some orange and apple segments and took the opportunity for a pee (the only one from the swim to the next morning – I lost A LOT of fluid!). Annie massaged my shoulders – I was making good time through keeping in the aero position on the bike, but the constant hunching was putting strain across my back. This short break – only a couple of minutes – was a great reset. This turned out to be very necessary as the part of the bike I found toughest was yet to come. From the big feed there was a climb – not very steep but long and a definite effort. It was hot and at the top there was not the lovely long descent one hoped for but a short drop and then a long, slow, steady, agonising drag for about 10km into a headwind, right at the most demoralising point on the course.

At my next feed around 130km in I even paused to have a cathartic moan to Nick (who’s Team Cherwell t-shirt was doing sterling work in identifying that it was indeed my crew at a feed stop – as there were plenty of pink supports T-Shirts (one per team, to allow them entry to transitions etc…) and a lot of Black VW Transporter vans that I could easily have got confused by) but I got underway again and was soon at the roundabout in Achnasheen (one of the few (3) junctions on the course), taking on the last 20km into T2 at Kinlochewe. Just before this the support crew left me, swapping my aero bottles (with plain water) to get on ahead to prepare for my arrival in T2. We’d driven into Scotland this way specifically to scope out the bike course and these last few kms are absolutely stunning. There is a small climb and then a sinuous descent down the valley – a ribbon of tarmac laid out before you. It makes the whole course worth it – all the slogging into headwinds, the heat, the midges and horseflies – all worth it for that. The Scottish roads don’t seem to have too many actual potholes (unlike dear Banbury) but it is quite rough tarmac, so I did have some pins and needles and pain in my feet and toes, but I knew I was on the home stretch. On the small climb I took a drink from the rear bottle, tipping my head back. This pressed my helmet against my forehead and a cascade of grey, horrible, sweaty water poured instantly into my eyes from the inside of my helmet. It stung horrifically and I couldn’t really see. I pulled over in a layby near the top and thanking my lucky stars I had water in my aero bottle and not energy drink I was able to rinse out my eyes, ready for the fantastic descent. Knowing the road, having driven it, and with no hidden obstacles I was able to give it the beans and hit my highest speed on the bike leg – in the last 20km no less – 78.7kph. I was delighted to roll into T2 in under 7 hours (6:58.31 ithankyew), with Annie taking my bike and ushering me to my heap of kit ready for the run.

In T2 we had made the decision to fully change into running shorts and tshirt. Especially with the heat on the bike my trisuit was pretty sweaty and I suspected that the salt crystals would chafe over the run. Annie had my Dryrobe ready in T2, which was pretty basic – just a field really – as there was no need for extensive bike racking as crew could take the bikes away, so I was able to get changed without scaring the locals too much, and I took the chance to sit down (my ever efficient crew having brought a camp chair from the van) and while I ate some orange and apple segments: refreshing but something to bite on, Annie rubbed some feeling back into my feet. I put on a hydration vest with water, gels and mandatory jacket in, and waving to Nick who was at T2 exit waiting to be dropped off at T2a, set off on the first half of the run.

The run is split into three parts T2 > T2a. T2a over the mountain to T2b, and T2b > Finish. On the mountain section having a support runner is mandatory. They can also accompany you on the other two sections. I was going to do the first section solo, and then the plan was for Nick to support from T2a to the finish (as at T2b there is really nowhere else to go except to the end). I would run the first section with one running/hydration pack, and then switch this out at T2a for a larger one with the more extensive mandatory equipment required for the mountain section. This would save carrying unnecessary weight for the first 18km. Any kit left at T2a would be ferried back to race HQ by the organisers. The cloud had closed in by this point, but rather than making it cooler the air was close, humid and oppressive.

I was feeling, if not fresh, pretty good so I set off through a small park – nothing technical in the first couple of km, just some tracks through small woods, and some gravel sections of path and a short section of road. I even made a few passes. The path began to get smaller and smaller and soon the gravel underfoot disappeared entirely. The way was just a narrow gap in the knee high heather and gorse, and I was wishing that I was wearing calf guards, not for any compression or support benefit, but just to stop the tough vegetation scratching my legs quite so much. Bits of Celtman tape tied to posts or stunted trees kept me on track. Being comparatively strong on the bike meant that some wiry trail running looking types came past me, some with support runners, some solo as I was. A small valley opened up in front of me, a steep muddy bank with some twisted roots down to a small stream. Quite frankly it was a swamp, insects were buzzing, the atmosphere was even closer and more humid under the trees. It was a scramble up the other side of the bank among the ferns, which were so high they made a tunnel and sweat was pouring off me. It was a relief to get out of the undergrowth onto a gravel track. This dropped down to an aid station where I got some jellybeans and coke to give myself a bit of a sugar boost. I was keeping on top of sipping from my hydration pack as it was still warm. After the aid station the path curved around some bushes and then it went upwards – really upwards. There was no choice but to walk, which was quicker than running (or attempting to run) anyway. It was very rough gravel and stones underfoot which was not as smooth as it looked, but at least progress was made. It climbed steeply for around 500m before flattening out through some gates and undulating round the edge of the hill. After a few of these small rises and dips. The path went down again, just a steeply as it had gone up – enough to get the knees nicely softened up for what was to come. At the bottom was another aid station, another chance to have a handful of jelly beans (more to have something to bite on than for the sugar – I’d taken a gel on the way down to get the energy hit) and it was only a few flattish km along the shore of a lake onto the road. I relaxed slightly at this point as I was pretty certain that I was going to make the 11 hours from start cut off to make it to T2a, to enter the mountain. A couple of km along the road and I caught sight of flags on the side next to a little track, that disappeared into the undergrowth heading directly for the sheer side of rock and grass – I’d made it to T2a with half an hour before cut off. As I approached a flash of lightning lit up the summit – it had been humid all day, and it could well be that a full on thunderstorm was brewing.

I jogged into T2a, glad to see that Nick was on hand as planned. I got off my hydration vest as I was going to need the bigger one Nick had waiting for me. We made sure that my GPS tracker and waterproof jacket were transferred over. I took the chance to have a brief pitstop in the portaloo and when done got my bag checked (Nick had already had his kit looked at). We actually set off in a small group of teams – a few who had got in before me had been held at T2a for 10 minutes, due to the lighting I had seen over the peak, but it seemed to have moved on. We set off along the path towards the base of the hill. The challenge ahead of us was clearly visible, so we were cautious not to set off too fast. The path very quickly went upwards, and jogging turned to walking which turned to climbing relatively quickly.

It was rather a trudge, we crossed a small stream and I doused my hat with cold water. Nick was checking in regularly, making sure I was taking on enough food and drink. It wasn’t just the steepness of the terrain that made it difficult – the actual ground underfoot was a little maze of paths and gullies, but these were filled with large pebbles and boulders and this made it difficult. They rolled and slid under our shoes, making a turned ankle or tumble a real threat. Nick was able to do some route finding and was identifying the best way forward. He found it was slightly easier to stay out of the little gullies and try to move between the small patches of grass, and he was spotting where the passage of feet had made little steps. It sounds simple but it was not always easy to spot where the better going was, and sometimes we had to snake from side to side – longer perhaps but almost certainly faster the trying to go straight up through the loose material. The course essentially goes up the mountain, along the top, and down the other side. The race organisers reserve the right to have an extra cut off at the top of the climb up 1 hour 45 mins after you leave T2a. Thankfully we were well inside this and I tagged my dibber having made the climb. We were then making our way along to the scree slope, just a few more metres on from the dibber point.

At this point though we started hearing a few calls from below, but we couldn’t make out what they were saying. However it filtered down to us from a few athletes above us that mountain rescue, who were positioned on the scree slope, were worried about a thunderstorm coming in and catching us on the exposed top. Under their instructions we dropped down a little way to the checkpoint to find out what was going on. Disappointingly they had made the call the conditions were worsening and it was too unsafe to let athletes onto the exposed ridgeline and scree slope. We’d done the bulk of the elevation on the course but we had to return down the same way – back to T2a. We found out later that only the first three athletes out of the whole field had managed to make the full high course route before the weather closed in – a few more had been turned back from the scree itself (which must have been really demoralising!) and a bunch of us who had made the climb checkpoint (within all cutoffs). Anyone who was still on their way up from T2a (although I don’t think that there can have been too many) was turned around by people coming down, as the mountain was closed. The descent was unpleasant – those rock filled gullies had been tricky enough on the way up, but on the way down they were even more treacherous, made worse by general fatigue, and my knees were taking an absolute hammering with the shock absorption. It was hardly glamorous, and even when the path flattened out back to T2a I couldn’t quite conjure a run. At T2a we were told to head down the road a couple of km to T2b – the point where we would have exited the mountain – where we would have a choice – we could go and do the full ‘Low Course’, or travel down the road back to Torridon and the finish. We set off and I immediately was hurting. It wasn’t my legs, but the soles of my feet. The coarse tarmac of the Scottish roads had already vibrated them into having pins and needles in T2, and running on the hard tarmac in off road shoes with knobbles on the bottom was tenderising them still further. It was like the entire surface that was in contact with the ground was burning. Nick was still keeping me supplied with nutrition and now he broke out the encouragement I needed. We began doing short sections of running. It was painful but I like to think these bursts did get slightly longer and more frequent (Nick may tell a different tale!) as we headed towards the finish. A few people did pass us, but as all the competitors had done slightly different distances, and indeed different courses, there was no way of knowing any sort of positioning or trying to compare yourself against other athletes, so I just kept plugging away.

The road does twist and turn between low hills, so you only see Torridon as you round the last bend before it. I was therefore quite startled to see Annie walking down the road towards us. She explained that you looped round the village so she would take the shortcut back to the finish to meet us, whilst we did the other two sides of the triangle. This spurred me to pick up the pace and I broke into a shambling run. I did manage to overtake another chap and therefore had to keep my run going a little longer, as I couldn’t quite bring myself to run past him and then immediately collapse in a heap.

The course cruelly twisted right to the other end (and bottom of the hill) of the village, so I was treated to the sight of the finish arch that I was running away from. Finally we ran through a small field I recognised (used as a carpark during race registration), turned right, and knew there were only a few hundred meters UPHILL AGAIN! to the finish. I’d been running for 6:31.15 and covered 34.3km, with 1200 metres of climbing. I crossed the finish line resplendent with its flaming torches, finally, after setting off at 5am that morning, having swum across Loch Sheildaig, biked through 200km of breathtaking scenery, and made all the high course cutoffs conditions allowed on the run, in a time of 14:51.22.

Celtman don’t do medals, they hand you a beer at the end and then point you towards a buffet. Priorities. In fact its remarkable in the athlete guide that interspersed at regular intervals among the information about mandatory equipment, race briefings and so on the bar opening times are clearly and consistently laid out. Excellent organisation. The next day we gathered for the distribution of Tshirts – blue for those who made the high level cutoff (which I proudly received) and white for the low level finishers. There was also a debrief of sorts, with many stories of the day shared – the support crews that had helped each other and other athletes, loaned bikes and overcoming difficulties in many small ways. A group photo of the finishers proudly wearing their tshirts was taken with the spectacular mountain backdrop behind.

We took a leisurely journey back, stopping off near Loch Lomond one night, and Ullswater in the Lake District another. Surprisingly I wasn’t too seized up – perhaps the slightly slower run pace and a shorter tarmac section have saved my legs from endless impact, although the steep descents had wrecked my knees. A few short walks were actually quite pleasant.

I hope its been clear that I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Annie and Nick on support (I should probably buy shares in a cider farm, the amount I’m going to have to buy for them), but also to Rich for his coaching – and adapting my training as I fell foul of all the illnesses and injuries. I’m not quite sure how he did it but he managed to get me to the start line in some sort of reasonable shape!

© 2023